Tyrannical Illiteracy

In this series of essays, I explore the causes behind the Western world’s regression into tribalism, conflict, and intellectual malaise. As a proponent of Marshall McLuhan’s assessment of digital media, I assert that we arrived at our current situation by being irresponsible consumers of media technology.

By ignoring the prophetic analyses of McLuhan, we brought our own civilization to its knees, allowing the arrival of the “global village.” There is nothing but aggression, conflict, and strife to be found in this village, and until media literacy becomes a commonality in our culture, we can expect to remain in this unfortunate state.

Part One presents how our tactile means for interfacing with our media has wreaked havoc upon our mental capacity, in particular by eradicating literacy — the foundation upon which rational thinking, logic, and science rest. Consumers’ careless sanctioning of new media technologies struck at the very essence of what makes Western thought both possible and practical.

Part One: How Tactile Interfaces Encouraged our Digital Tribalism

Marshall McLuhan wrote extensively on the virtues of text — namely, that it promoted literacy, which in turn enables specialization. He saw that an empowered specialist was able to dive more deeply into their area of interest, and thus precipitate an ever greater technological need for improved means for storing, recalling, and citing textual information.

By examining the television industry’s ability to broadcast images just as radio succeeded in broadcasting speech, McLuhan then made a bold prediction: that specialists would one day be able to digitally request all of the text relevant to their needs, and have it delivered to them instantaneously.

This early prophecy came true with the invention of the Internet. The pre-WWW web was indeed a highly categorized ecosystem of knowledge, held together by a standard called Gopher. This early web technology provided a means for cataloging the information stored at a particular destination. There were no fancy colors, flashing banners, or images of any kind. Just a series of folders, upon folders, upon folders.

A university’s “Gopherspace”. Go to any university’s website today, and tell me it’s better-organized than this approach from the early-1990s.

For the “empowered specialist,” Gopherspaces (as they were once called) represented the very best environment for literacy. It provided a standard means for information taxonomy, reduced network traversal to its fundamentals, and operated with a familiar, yet highly evolved input mechanism: the computer keyboard.

Literate individuals were familiar with the computer keyboard thanks to their experiences with typewriters. So this new digital interface was both easy to navigate and deeply enticing, since the computer keyboard delivered possibilities that were previously unknown to the world.

To be an early internet user was to be simultaneously intrigued and empowered. It was a hyper-accelerator for curiosity, giving the user a means to move and to reason as quickly as they were able to think. An 80 words-per-minute typist could make new connections and draw new intersections, thanks to this ability to jump between different topics effortlessly.

Eventually, the Internet and its burgeoning industry came to a crossroads, and the decisions that were then made irreversibly re-shaped the world. Gopherspace fell out of favor to the world-wide-web, which made much more liberal use of screen space, decoupling the interface from the protocol. With content creators able to assert any interface they wish through the Internet, new kinds of standards arose. No longer was it essential to make use simple, predictable, and efficient — instead, the Internet became ‘productized’ like so many brands of cigarettes, beer, and automobiles decades earlier. Design forced the Internet to base user interaction decisions demographically, rather than democratically.

And so, the primary means for navigating the Internet had to change. Cooling down the Internet in the fashion of Tim Berners-Lee’s world-wide-web led to the implementation of a form of digital tribalism never before seen in the Western world. But to understand how this happened, another important concept put forth by Marshall McLuhan must be explored: the dichotomy of “hot” and “cool” media. The best way to illustrate this is to examine the differences between film (hot) and television (cool).

Consider the video media of today and its historic progression. Things got started with the “hot” medium of film, an art form of relatively high resolution, which requires the viewer to focus, interpret, and think. McLuhan identified such media as literate media, because it asked much of the viewer’s mind in real time, quite similar to how literature demands the reader’s constant mental attention.

The same judgments cannot be made of television, which resulted from a culmination of efforts to “cool down” the content of film. TV provided rapid selection and multiple choices to viewers, and also placed the content in the viewer’s living room, where it became a part of the general environment, rather than a specialized event requiring specific focus to enjoy. The television viewer did not change their environment to cater to their content; the lights stayed on, people were forgiven if they stepped in the way of the screen, and even to this day, stereo audio is preferred over the all-encompassing surround sound of the movie theater. All in all, TV made video simpler to understand, easier to approach, and less expensive to consume.

But the reason why TV enjoyed such massive success is because it introduced a new means for interacting with the content: the remote control. Without it, making use of TV’s cooled down, less literate video would have been tedious. Television encouraged viewers to “channel surf,” which meant that the content creators could not rely on viewers’ focus and dedication. So, the content became optimized to suit the medium. Shows became formulaic, to the point where specific storytelling strategies were leveraged to attract a specific demographic. Moments of intense excitement were conceived of to grab a passive consumer’s attention. Nuance and storytelling did not fit into this new delivery mechanism, so the literate arts were given less and less attention. Statisticians took the place of the storyteller, to fit the new medium. The medium is the message.

In the early 1990s, personal computers put a new kind of screen in everyone’s homes, and it didn’t take much time until people realized that with some tweaking, it too could usher in a new form of cooled down interactive entertainment. All that had to happen was we had to introduce a new means for exploring and manipulating the content on the screen. That way, the design-heavy, tribalist world-wide-web being conceived at the time could be navigated with ease by the average consumer. Enter: the computer mouse.

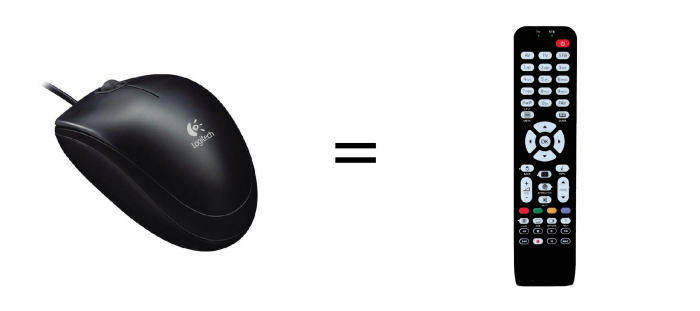

Tactile inputs democratize media technologies, easing media consumption by placing it within the public environment of the viewer.

The invention of the mouse brought with it not just a new kind of user, who did not need to rely on their prior literacy to learn this foreign technology. It also conjured up a series of precedent-setting trends that forced organized, literate protocols like Gopher into extinction. And while nobody knows the etymological origins of the mouse, it seems a fitting moniker. It is, after all, a device which causes its users to act very much like a small rodent frantically searching a man-made maze for the hidden cheese.

Point-and-click inputs, like those facilitated by the mouse and the TV remote, abstract away the actual function the user wishes to enact, by encouraging the use of tactile senses to explore the environment. So, while a keyboard-driven interface asks the user to learn the system and then optimize their use patterns for efficiency and explicitness, a mouse does the exact opposite: it asks the user to hunt and peck at their own whim, to find what they are looking for via intuition. Even if many human societies have excelled at the hunter-gatherer mindset required of the computer mouse user, there should be no arguing the relative illiteracy of these traits.

Tactile interfaces cool down the media landscape, and force new forms of tribalism into the collective consciousness. If keyboards and Gopherspace find their historical equivalency in the library catalog cards of yore, then the mouse and remote are akin to frantically looking for your lost car keys moments before you’re supposed to be leaving the house for work. When you’re working with mainly text, still the stuff that underpins the Internet, which type of interaction would you prefer to utilize?

Most have chosen the latter, preferring the methodology that requires less reading and instills greater frustration, aimlessness, and uncertainty. To me, this makes quite a statement about the state of our minds and their inherent tendencies.

Marshall McLuhan used to point out the folly of introducing new technologies to illiterate peoples:

The hot radio medium used in cool or nonliterate cultures has a violent effect, quite unlike its effect, say in England or America, where radio is felt as entertainment.

Indeed, storytelling in a cool culture requires the visual component of being present, whereas Western culture enjoys applying its literate mind to the orated word. By supplementing production values in place of a speaker’s facial expressions, radio encourages the same type of “rapid guessing” that film and literature demand from its consumers.

The Internet of the 1990s provided the very hot medium of text, surrounded by distracting visual designs, all via a highly tactile navigation mechanism. People were “rapidly guessing” at a scale never before seen, as our careless design trends took on new significance and power with each passing moment. The end result of this new medium was an entire generation of Western minds consuming a kind of information far too hot and literate for the means being used to consume it.

When this form of consumption becomes the norm in a culture, it can be all too easy to propagandize its citizenry. Rapid guessing will inevitably lead to mistakes, and within the boundaries of these rapid mistakes lies the capability for a malicious actor to embed a false message for some form of material gain. It is within these malicious boundaries that the Western world finds itself today. Since the introduction of the world wide web, hardware manufacturers have been under constant pressure to conceive of new ways to catch the attention of the digital citizenry. After making valiant attempts with the Pocket PC and keyboard-driven phones like the Sidekick and Research In Motion’s Blackberry, Steve Jobs finally figured out how to make an even more tactile interface that could achieve the advertising industry’s ambitious goals.

Apple’s introduction of a smartphone with a functional, highly intuitive touchscreen interface brought the end to the mouse’s dominance. The smaller screen size meant there was less to peck around for than on a conventional mouse-driven computer, while haptic feedback provided even more instantaneous reaction to user input than before.

Apple’s iPhone provided a form of tactile input that the computer mouse simply could not match. There is nowhere left to hide from the digital tribalism this form of media introduced to the world.

The first iPhone famously shipped out to users without any copy-paste functionality, yet it did not matter one bit to end users; the prominence of the literate Western mind had already declined thanks to two decades of mouse-driven digital life. Understandably, users were far too impressed by the ability to sync one’s iTunes library to their cell phones to notice that final stake being driven into the heart of our collective intellect.

Even if consumers were able to pry themselves away from all the new goodies introduced by the modern smart phone, they wouldn’t have been able to do much about its immediate global impact. Combined with an extremely well-executed marketing campaign, Apple left no room for our minds to breathe, compelling us to disassemble our literacy, the last remaining prestige of Western culture. With this, came the fulfillment of Marshall McLuhan’s prophecy: the advent of the global village.

In Part Two of this series, I will explore how democratization of media technology led to an unprecedented global adoption of a simultaneously hot-and-cool content ecosystem. Once again, I invoke the genius of McLuhan to foreshadow what is to come:

The global village is a place of very arduous interfaces and very abrasive situations.